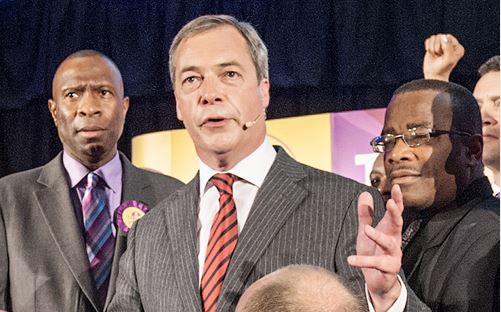

Asian Lite looks in to the consequences of euroskeptic’s victory in the EU elections

victory in the EU elections

Anti-euro and anti-orthodox parties now account for at least a third of seats in the European Parliament. While the swing towards anti-Europe parties UKIP and the Front Nationale were widely anticipated in the UK and France, Germany’s anti-euro AfD party won parliamentary representation for the first time, with 7% of the votes.

The far right also made gains in states which have more recently slumped, including the Netherlands. Cebr analysis of how far many European countries still are from their 2008 GDP levels makes the cause of dissatisfaction clear.

Cebr expects that for 2014 as a whole, the economy of Spain will remain 6.0% smaller in real terms than it was in 2008, while the economy of Greece will be 23.3% smaller than it was six years previously. Despite a tentative return to growth, the Irish economy is expected to remain 3.9% smaller than it was in 2008, and the Portuguese economy will still be 5.8% below its 2008 peak size. And for these economies, recovery is not just around the corner; each will bear the scars of recession – high unemployment, continued austerity and reform fatigue – for years to come.

Other EU states, meanwhile, have weathered the crisis relatively well. By the end of 2014 Cebr expects that German output will be 5.0% higher in real terms than in 2008. Other economies, including Italy and France, have managed to secure some economic growth over the last six years, but face substantial structural challenges ahead, and are likely to see slow, bumpy recoveries.

This patchwork of economic circumstances across the Eurozone highlights the new dimensions of anti-euro challenges. Both those who have done well during the crisis and those who have suffered seeing reasons to leave the currency union.

While the new-found strength of anti-Europe groups in the parliament will not have any immediate effect, it will undoubtedly emerge as a stumbling block in the process of European reform. As citizens in both those countries who have rebounded since the crisis, like Germany, and those who have struggled since the crash, like Greece, made their displeasure with the currency union known, the task of protecting it will get harder. As the financial and economic footing of the Eurozone becomes more secure, politics may yet undermine the project.

Danae Kyriakopoulou, Cebr Economist, said: “Despite recent improvements, Europe’s crisis has exposed the need for further integration in order to secure the future of the currency area. May’s elections however have highlighted a harsh contrast between this economic need for such integration reforms and the electorate’s lack of appetite for it. This is a serious downside risk for Europe’s economic prospects: political uncertainty and instability will make businesses less likely to invest, and the lack of cohesion on the political stage will provide a big challenge to the push of much-needed reforms.”