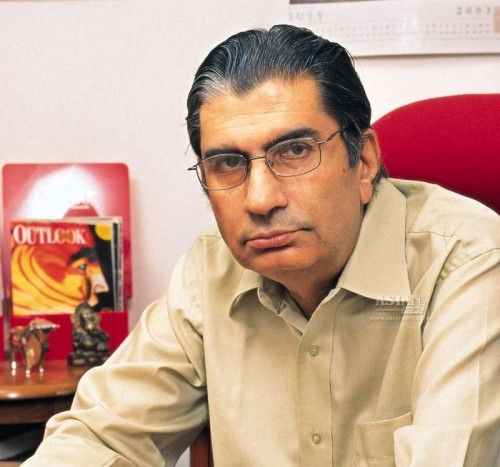

Vinod Mehta, one of India’s best known journalists, died here of multi-organ failure, doctors said. Prime Minister Narendra Modi called him “a fine journalist”.

The 73-year-old Mehta, who at one time worked as factory hand in Britain, passed away at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), its spokesperson Amit Gupta said.

AIIMS said Mehta suffered from several neurological issues and had been bed-ridden for three to four months. He was admitted to AIIMS in critical state last week.

Outlook group, which was the last major media group Mehta founded, announced the death of its founder-editor-in-chief “with deep sadness”.

Even after ceasing to be its editor, he was its editorial chairman.

Modi said in a tweet: “Frank and direct in his opinions, Vinod Mehta will be remembered as a fine journalist and writer. Condolences to his family on his demise.”

Born in Rawalpindi before India’s partition, Mehta’s family moved to India when he was only three years old. He grew up in Lucknow, studying in the La Martinere school and Lucknow University.

His big moment came in 1974 when Mehta, at age 32, took up editing “Debonair”, a men’s magazine in India which boasted of serious articles as well as centre-folds.

He later went on to launch other successful publications such as Sunday Observer, The Pioneer and Outlook. He also founded the Indian Post and The Independent newspapers.

A gifted writer, Mehta authored a biography of Bollywood actress Meena Kumari and Sanjay Gandhi, the younger son of slain prime minister Indira Gandhi. His much acclaimed memoir, “Lucknow Boy”, came out in 2011.

Home Minister Rajnath Singh, the Bharatiya Janata Party MP from Lucknow, said: “I express my heartfelt condolences… His demise has left a big void in the field of journalism.”

Vinod Mehta ventured into areas where lesser mortals might have feared to tread — either for fear of taking on the establishment or simply because it went against the normal credo.

He staked his reputation by declaring Narendra Modi as the next prime minister, despite being highly critical of the man. At that time, every journalist worth his salt argued passionately that it would never happen, given the country’s complexity, size and identity politics.

One of the most acerbic and irreverent of mainstream scribes, he never minced words about politicians or fellow journalists or even spared himself.

“I am a very verbose kind of person,” he had once told an interviewer, with an unflattering candour. The self-depreciating Mehta also said that some people have even labelled him a “Congress chamcha”. He also had a dog named Editor.

Mehta shared a love-hate relationship with news channels, dubbing half of their content as a joke. “I speak rubbish on TV debates,” he quipped, “yet I’m called again,” he told a popular daily.

Mehta came from a diminishing class of journalists who considered TV a notch below the print media. But he confessed to being flattered when people recognised him at the airports. He considered it to be a “nerve wracking” experience to appear on TV.

Controversial as he might have been, Mehta never compromised with his values, no matter what happened.

During his stewardship of Outlook weekly magazine, he went ahead with his shocking revelations on the Radia tapes in the telecom scam.

In spite of knowing that the expose would damage the credibility of individuals and organisations, besides antagonising large sections of his fraternity, he stood his ground, unaffected by pressures or the barrage of criticism.

He believed that those who had an ethical and social responsibility towards society should not be compromising their values for the sake of self aggrandizement. But then the aftermath hit his empire like a tsunami.

A reputed corporate entity blacklisted the magazine. Prominent journalists boycotted Mehta. A news channel banned him from its programmes, though it must be said that he had published their version.

Two years after the disclosure of Radia tapes, Mehta found himself reassigned to a ceremonial role, as the editorial chairman, after helming the group for 17 years.

“Radia tapes,” he told scroll.in, a media website, “are a benchmark in seriously damaging the reputation and credibility of journalists, both electronic and print.

“The public at large still thought that we are great patriots, we did things in public interest, we would never publish things that were inaccurate, that we would not be swayed by monetary or other considerations.”

In opinion polls too, journalists made it to the top 10 corrupt professionals.

Controversy continued to dog Mehta’s footsteps, often described as “brutally honest and frank”.

Indian Express slapped him with a Rs.100 crore defamation suit, after he hinted darkly in an interview with Open magazine, that the story on the movement of the two army columns and the alleged coup attempt was planted.

The government of the day refuted the news, coming in the wake of tensions generated by then Army chief Gen. V.K. Singh’s date of birth.

An unfazed Mehta coolly told the Mumbai Mirror: “What’s the fuss, he (Shekhar Gupta) is perfectly entitled to sue me if he wishes to.”

Although Mehta went through a very tumultuous phase between 2010 and 2012, towards the fag end of his career, they formed a small part of his illustrious career.

He had penned a succession of books over the years, beginning with “Bombay: A Private View” (1971), followed by “Meena Kumari” (1972), “Mr Editor, How Close Are You to The PM” (1999), “Lucknow Boy: A Memoir” (2010), “The Sanjay Story” (2012) and “Editor Unplugged: Media, Magnates, Netas and Me” (2014).

“Editor Unplugged”, a sequel to the “Lucknow Boy”, has been described as an “honest, lively and irreverent” book, “both illuminating and entertaining”.

A reviewer at the amazon.in site says: “Vinod Mehta gives his unvarnished views on the media magnates he worked for, the colourful people that he interacted with, about politicians, about industrialists, arrivistes, frauds and a whole lot of other issues … the sweep is wide.”

Mehta did odd jobs after graduation, before taking up his first assignment in 1974 as editor, Debonair, the country’s first adult magazine. It helped a generation of Indians grow into adulthood.

Later, he successfully launched the Sunday Observer, Indian Post, The Independent, The Pioneer (Delhi edition) and finally, Outlook, where he found his forte. He became a Delhiwallah and was married to Sumita Paul, a journalist.

Mehta, born on May 31, 1942 in Rawalpindi, migrated with his family to India in 1945 and settled in Lucknow.

He grew up in Lucknow’s inclusive culture, which shaped him as an incorrigible ‘secularist.’ He attended La Martinere school and the Lucknow University there.