India’s tourism icon and a symbol of earthly love, the 17th century white marble mausoleum, the Taj Mahal, is a victim of both nature and man. If the monument looks sick and pale to visitors, the reason is the dry and heavily polluted Yamuna that once formed an integral part of the Taj Mahal complex.

Standing tall in the scorching summer sun, the monument of love is enveloped in yellowish sand from the neighbouring Rajasthan desert. Any discernible visitor can tell that the summer heat is taking its toll on the Taj Mahal, the timeless monument of love, blasted by sand from the dry Yamuna bed and the dust-laden winds from the Rajasthan desert.

The gaps left by illegal mining in the Aravali ranges have raised the SPM (suspended particulate matter) in Agra. Against a standard of 100 microns per cubic metre, it remains as high as 300, touching 500 during summer months. The problem is that sandy particles rub against the monument and leave pock marks that make the surface rough, as has been pointed out by many studies.

However, conservationists say that the crisis the Taj confronts comes not merely from nature and pollution but also from people themselves – too many tourists and too many vehicles that bring them to Agra. The number of vehicles in the city has shot up from around 40,000 in 1985 when Firozabad too was part of the Agra district, to more than a million now. The opening of the Yamuna Expressway has increased vehicular traffic, while the pressure of heavy vehicles on the Delhi-Kolkatta and Delhi-Mumbai national highways passing through Agra has increased phenomenally.

Adding to its fatigue is the ever-increasing human load. From a few hundred daily some decades ago, the Taj today is daily visited by thousands. Last year six million tourists visited the fragile monument. This number does not include children below 15 years for whom entry is free. For five days in a year the entry to the monument is free for everyone. The tourism industry that thrives on milching the Taj Mahal wants more sops for visitors to attract more visitors, but the conservationists want restrictions imposed to gradually reduce the human load.

Surendra Sharma, president of the Braj Heritage Society, wants graded entry fees and online ticket booking. “The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) must fix a limit on visitors. Booking can be done online to restrict the number and prevent alleged re-sale of entry tickets,” he says.

Visitors who see the Taj Mahal for the first time never forget to ask the guides: “Is it turning yellow?” The explanation given by the guides is that it is the natural ageing process and has nothing to do with industrial pollution, as all polluting industries in the Agra region have been shut down by the Supreme Court.

To ensure dazzling whiteness and remove stains left behind by pollutants on the Taj Mahal, originally called Bagh-e-Baahist, or heavenly garden, the ASI carries out periodic “Multani mitti” (Fuller’s earth) treatment. The white marble surface is also washed with soap and water Fridays, when the monument breathes freely on its weekly off.

“When thousands of tourists invade the serene monument every day, leaving behind hand and foot marks on the white stones and tonnes of noxious gases through breathing, the cumulative affect on the fragile structure is huge. Only a few tourists are genuinely aware of the historic significance of the monument and its great heritage value, there are hordes of others who care nothing for the sanctity of the Taj,” Rajeev Tiwari, president of the Tourism and Travel Agents Association, told IANS.

“Each Friday, when the mausoleum is closed for tourists, the Muslim faithful are allowed free entry to offer prayers. During the annual Urs of emperor Shah Jahan, the entry is free for three days and the number exceeds 50,000 daily,” he added.

Tiwari recalled that in the past, a visit to the Taj was “almost like a spiritual journey to a shrine”.

According to heritage photographer Lalit, “the hyped-up romanticism attached to the monument and the guides spinning out cheap gossipy yarns to titillate the tourists have in a way defiled the sanctity of the structure”.

Abhinav Jain, a tourism industry leader, said: “The mausoleum must have been originally designed for 50 or 100 visitors a day. But now there is no end. With the tourism department and the Agra Development Authority making extra efforts to promote tourism, the number will continue to rise.”

According to Jain, there has to be a better way of regulating visitors inside the Taj.

“It is time they had a system in place allowing a specific number of visitors inside the Taj for a fixed period. Also online reservation facility should be made available so that the entry is orderly and spread out,” he added.

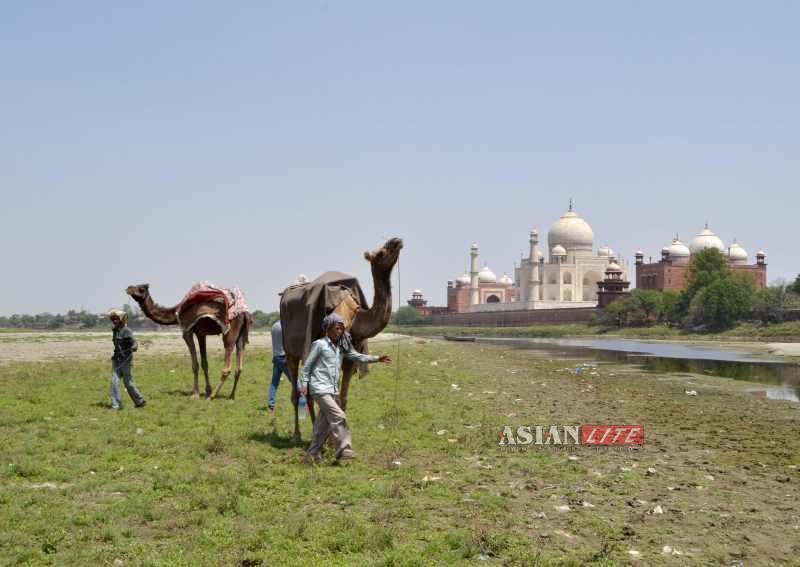

While the human load problem will be sorted out shortly, as a number of studies are being conducted by the ASI, the sad state of the Yamuna river at the rear is a huge problem that defies solution. According to Ved Goutam, a tour guide, Agra has already become a desert.

“When you see the camels moving around on the dry river bed, one gets the impression that Agra is in a desert, a part of Rajasthan,” he said.

The ASI has restored the Mehtab Bagh at the rear of the Taj Mahal and the state forest department has developed a dense green buffer along the river bank on the opposite side.

But the major problem is the Yamuna, which has been reduced to a “sewage canal”.

Shyam Singh Yadav, a retired chief horticulturist of the ASI, said: “It was a herculean task developing a well laid-out green heritage garden behind the Taj.”

However, conservationists are skeptical whether this small patch of green can insulate the Taj from the high SPM level at the peak of the summer.

“If there is no fresh supply of water in the river that touches the Taj foundation to provide a shock-absorbing buffer to insulate the building from seismic movements, the fear is that the monument could tilt, cave in or struggle for stability,” fears eminent Mughal historian R. Nath.