Vikas Datta looks into Terry Pratchett’s Discworld novels

No tyranny – be it a repressive regime or of outmoded customs and entrenched attitudes – can withstand the subversive sound of laughter. From the earliest times, perceptive observers of the human condition have used the devastating literary weapon of satire to ridicule the vices, follies, and abuses of their times in a bid to shame people, government or society itself and nudge them to improvement. More often than not, they have been successful in inspiring revolutions – political and social – or even the more difficult task of changing mindsets or showing the shallowness of several pursuits which occupy time and attention of society. Terry Pratchett is among those treading the latter road.

No tyranny – be it a repressive regime or of outmoded customs and entrenched attitudes – can withstand the subversive sound of laughter. From the earliest times, perceptive observers of the human condition have used the devastating literary weapon of satire to ridicule the vices, follies, and abuses of their times in a bid to shame people, government or society itself and nudge them to improvement. More often than not, they have been successful in inspiring revolutions – political and social – or even the more difficult task of changing mindsets or showing the shallowness of several pursuits which occupy time and attention of society. Terry Pratchett is among those treading the latter road.

Sir Terence David John “Terry” Pratchett (born 1948) draws on an impressive range of well-known works, including of William Shakespeare, J.R.R. Tolkien, H.P. Lovecraft, popular culture, mythology and folklore as well as historic events to create satirical parallels with many political, economic, cultural, scientific and sporting issues in the 40 works of his Discworld series.

Taking the path fashioned by illustrious forebears like Jonathan Swift and Voltaire, who created imaginary lands to base their satires, Pratchett created Discworld – a flat world held up by four elephants standing on the back on a giant turtle flying through space – as the setting of his works with the openly avowed aim of “having fun with some of the cliches”. Divided into various continents, regions and countries – many of which will strike a chord – the Discworld seems to be in the late medieval/early modern age though various new technological, social and cultural innovations – which we will find familiar – keep cropping up.

The Discworld series was not the first from Pratchett’s pen since he had been writing from over a decade before and already had several published works but has become his definitive work apart from being hugely successful – selling over 80 million copies in 37 languages. Since the first “The Colour of Magic” in 1983 to “Raising Steam” in 2013, the series now stands at 40 novels, not to mention 11 short stories, four popular science books, and the supplementary books and reference guides.

The Discworld series was not the first from Pratchett’s pen since he had been writing from over a decade before and already had several published works but has become his definitive work apart from being hugely successful – selling over 80 million copies in 37 languages. Since the first “The Colour of Magic” in 1983 to “Raising Steam” in 2013, the series now stands at 40 novels, not to mention 11 short stories, four popular science books, and the supplementary books and reference guides.

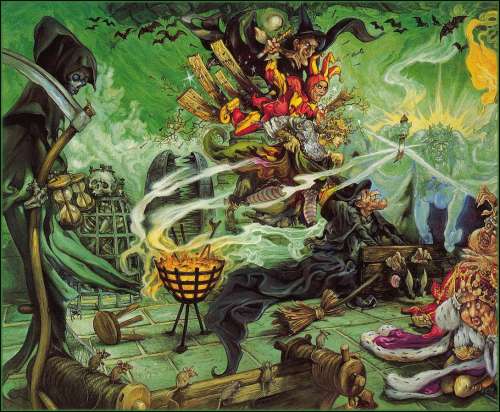

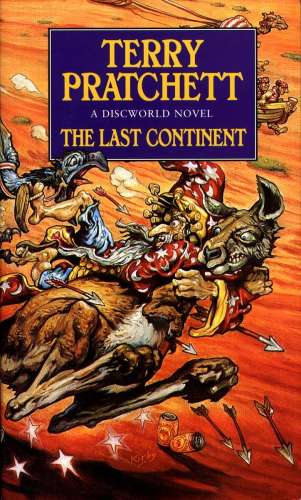

To some extent, the Discworld canon contains stand alone works set in the same fantasy universe, but a number can be grouped together into story arcs dealing with particular characters or set of characters, chiefly the inept and cowardly wizard Rincewind, the anthropomorphic personification of Death, who appears in almost all the works, a coven of witches, the Wizard fraternity of the Unseen University led by Archchancellor Mustrum Ridcully and the orangutan Librarian, Ankh-Morpork’s Patrician (or ruler) Lord Vetinari, its City Watch or the police force, led by the hard-bitten and cynical Sam Vimes, and in most of the recent works, con-man-turned-all purpose administrator Moist von Lipwig.

The plots show Pratchett as his most vividly ingenious and inventive. Various fantasy cliches and sub-genres are parodied – fairy tales (“Witches Abroad”), vampire stories (“Carpe Jugulum”), the Arabian Nights ethos (“Sourcery”), as well as works like Shakespeare’s “Macbeth” and “Hamlet” (The Wyrd Sisters”), the Faust and Homeric legends as well as Dante’s “Inferno” (Eric).

But where Pratchett shines is when he deals with our world’s issues, transferred to the Discworld, such as religion (including in its most intolerant form) and the power of belief in “Small Gods”, business and politics and modern banking in “Making Money”, and arts like opera (and the Phantom of the Opera) in “Maskerade”, rock music in “Soul Music” (which echoes the story of Buddy Holly and the Woodstock Festival) and the advent of cinema in “Moving Pictures”.

Then, he focusses the apocalyptic scenario (“The Last Hero”), martial arts (“The Thief of Time”), modern football, sports fandom in “Unseen Academicals”, which also deals with fashion and modelling, university rivalries as well as race prejudice – and existential philosophy!

Another inspiration is the introduction of a modern innovation such as a police force in “Guards! Guards!”, guns in “Men at Arms”, submarines in “Jingo” (which also splendidly parodies David Lean’s “Lawrence of Arabia”), investigative journalism and the media business in “The Truth”, the postage stamp in “Going Postal”, and the steam engine in “Raising Steam”. But Pratchett also incorporates several other motifs that define (and plague) our history, society and science such as city planning and suburban expansion, terrorism, gender roles and justice, exploitative labour, ethnic strife, extremism and demagoguery, not to mention time travel paradoxes, the multiple-universe theory, chaos theory and so on.

Sadly, the onset of Alzheimer’s in Pratchett (diagnosed in 2007) slowed his output, while his novelist daughter is being prepared to don the mantle when he becomes incapable. But no one excels him in the alternative view of our world and its preoccupations and if you have not read him so far, start now!