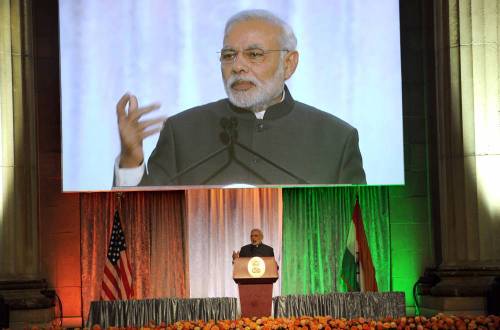

Top commerce ministry officials met Prime Minister Narendra Modi to finalise India’s position on the impasse over signing an agreement to ease global customs rules at the World Trade Organisation (WTO), an official source said here.

Top commerce ministry officials met Prime Minister Narendra Modi to finalise India’s position on the impasse over signing an agreement to ease global customs rules at the World Trade Organisation (WTO), an official source said here.

India has asked for a permanent solution to the issue of public stockholding for food security purposes and not a restricted period of four years as was originally decided during the WTO ministerial meeting in Bali, Indonesia last year.

Last week, WTO director general Roberto Azevedo unveiled three options to break the current deadlock over the Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA), that aims to ease customs rules.

“Clearly some members are already talking about alternative ways to take the TFA forward,” Azevedo said, adding that one of the ways could be to “seek implementation of the TFA as a plurilateral agreement outside the WTO.”

A crucial meeting of the WTO in Geneva in July to simplify the procedures of global commerce had failed to reach a conclusion, with India demanding as a quid pro quo some concessions for itself and other developing nations on food subsidy.

A success of this meeting would have signaled the first major step forward in the 19-year history of the WTO. The developed world especially looked forward to ratify this pact at the 10th ministerial conference next year.

India, per se, was not opposed to the pact on what is called trade facilitation when the diplomats from the 160 member countries met in Geneva and set July 31 as an informal deadline to sign on the dotted line.

Yet, at the core of New Delhi’s demand was food security for its 1.25 billion people, the bulk of whom live on government doles in the form of subsidised grain. This is also a guarantee under Indian statute, having enacted the National Food Security Act, 2013.

India wanted to take no chances, having been short-changed in the past. Its opinion mattered since the WTO is a consensus-based multilateral body.

This programme is set to cost the exchequer Rs.1,31,086 crore ($21 billion) annually and there was no way the Indian interlocutors could have conceded to a pact that could have potentially gone against a domestic law, as also the larger issue of food security.

Related to it, India wanted concrete action plan on two more aspects – subsidy to farmers for buying plant nutrients and periodic announcement of a minimum support for farm produce fixed by the government for its food distribution programmes.