By Trina Joshi

By Trina Joshi

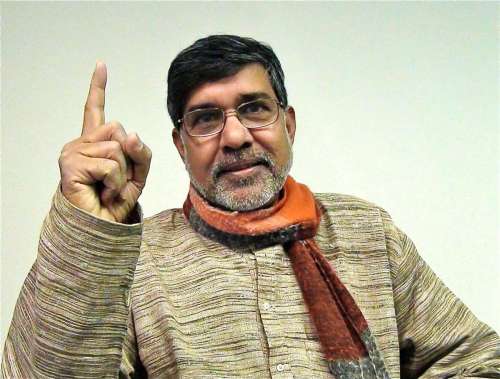

Terming child labour in India as a “serious” problem, the country’s newest Nobel laureate Kailash Satyarthi has said the delay in enacting and enforcing a ban on all its forms is akin to “destroying childhood” as our “children cannot remain trapped in workplaces”.

But in the same breath he sounded optimistic that the scourge would become history during his lifetime and the key, he said, was “quality education”.

In a detailed interview, the 60-year-old Satyarthi shared his thoughts on the bane of child labour that confronts India.

“One can’t say for sure how many children work as labourers, but there is a general consensus that there are about five million trapped in this unlawful activity,” the Delhi-based child rights advocate said.

“We can’t say with confidence that India is on the path of progress. So education is the key. Quality education has a direct link with substantial economic growth. An educated workforce and growth require good quality education,” said Satyarthi, who founded the Bachpan Bachao Andolan (save childhood movement).

Satyarthi, who shared this year’s Nobel Peace Prize with Pakistani child rights activist Malala Yousafzai and was awarded the distinction at a gala ceremony in Oslo, Norway earlier this month, was happy that the Narendra Modi government was concerned about the cause and was laying a special emphasis on education.

However, “quality education is impossible without total abolition of child labour in all its forms. Children can’t remain trapped in workplaces, mines, and in bonded labour.”

Satyarthi projected the problem of child labour in the country as “serious”.

Firm in his stand on the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Amendment bill, 2012, which has been stuck in parliament for over two years, Satyarthi said: “The delay in enacting and enforcing such progressive laws means destroying childhood. Millions of children are at a loss.”

“I have been urging the government to pass the amendment bill. It prohibits all forms of child labour up to age 14 and prohibits hazardous child labour till the age of 18, ” said Satyarthi, who is also a co-founder of the Global March Against Child Labour that is active in 144 countries.

Stressing on the need for banning child labour, Satyrathi said over 70 countries have passed the international law to combat the worst forms of child labour”.

“This awareness has become part of the corporate social responsibility as well. They can’t ignore the issue of child labour any more. It has emerged as a huge issue in talk and practice. The trend is positive,” Satyarthi said.

Narrating his journey of struggle, he said: “My biggest achievement so far is that I made child labour an issue in India and globally. But it was never easy for me three decades ago when child labour was a non-issue and people wouldn’t take me seriously.”

“I would then be reminded of Mahatma Gandhi’s words. He had once said, ‘First they ignore, then they laugh, then they fight, and then they finally win’. So I won’t claim that I have won the battle, the war is very big. But I am sure that in my lifetime, I will see the end of child labour,” said Satyarthi, sitting in his modest office in south Delhi’s Kalkaji neighbourhood.

“Generations to come will read in history books that there was an evil called child labour in India.

“It’s not just my optimism but based on concrete evidence and trends. Globally, 15 years ago, there were some 260 million child labourers. It has come down to 168 million now. The trend is clear,” he said.

In Satyarthi’s opinion, the Nobel Peace Prize is a potent signal to all the child rights activists across the world that the award belongs to all of them.

On his experience sharing the honour with the Pakistani girl, Satyarthi said: “It was more like family bonding as a daughter and a father. She said I was like her aboo (father).”

With several interests in common to discuss, they agreed, in principle, “to push forward our common agenda, especially the education of girls”.

Youngest among four children and the most pampered of all, Satyarthi was born to a family of modest means. And the seeds to fight child labour were sown very early on. It was all a moment of inspiration for five-year-old Satyarthi when he saw a child his age working as a cobbler outside his school. The sharp contrast stuck with him.

With plenty of questions simmering in his young brain, Satyarthi approached his elders to explain the disparity he observed.

“For a five-year-old, it was a big question. Why are some children born to work while others have access to education?” he asked.

He even accosted the cobbler’s father who summed up the disparity in one sentence: “We are born to work.”

“I was not satisfied with that answer. That was the first inspiration and a challenge to do something. It was like sowing a seed,” Satyarthi said.