By Ashis Ray

By Ashis Ray

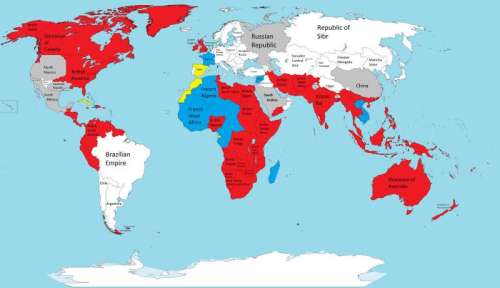

The expansion of the second and more recognised British Empire amounted to a formidable amassing of territory since 1497. Quite accurately, at its prime, the sun never set on the British Empire. However, the beginning of its end was the loss of the “jewel in the crown” – India – in 1947, following which its shrinkage galloped.

That there would come a day when the dilution of this Empire would reach a stage when Britain would be threatened with the shedding of a piece of itself was unimaginable. Yet, a referendum in Scotland Thursday will reveal whether this segment of the United Kingdom will continue to be an integral part of it or become an independent country.

The Scottish Nationalist Party (SNP), whose demand for Scotland’s separation from the UK has culminated in Thursday’s plebiscite, was formed in 1934. But it was not until 2007 that it achieved a breakthrough, forming a minority government, before winning a majority in 2011 in the Scottish assembly.

In 1707, the Scottish and English parliaments each passed an act to constitute a combined legislature of the United Kingdom of Great Britain. The Scots needed financial support from England and access to the latter’s colonial markets for trade, while the English wanted to ensure Scotland would not align itself to another country.

The move wasn’t universally popular, though; and Scotland’s nationalist poet, Robert Burns, lamented the signing of the Act of Union by penning: “O would, or I had seen the day That Treason thus could sell us.”

The SNP’s shrill cry for disengagement is purely an emotional plea. In the distant future a divorce may not be unfeasible, but in the short, even medium term, a split from the UK from an economic perspective is potentially suicidal.

The debt of Scottish banks in an independent Scotland would, for instance, be 12.5 times Scottish GDP. The state would not even own the North Sea oil it now benefits from. The governor of the Bank of England – Britain’s central bank – has repeatedly stated such an entity would no longer share the pound as a currency. And Spain would most likely oppose its membership of the European Union, what with Basque separatists and Catalans within its borders getting emboldened by the Scottish example.

Business after business have warned against a de-merger from the UK. Retailers have highlighted that the economies of scale achievable as a result of 64 million British consumers would be unviable for just a 5.3-million Scottish market. The Financial Times and The Scotsman newspapers have categorically pegged their masts to the “No” cause.

The “Yes” campaign stems from an impression among a significant section of Scots that in a united Britain they are subservient to the English. But to imagine Scotland can flourish in the near future on technology and tourism, the sale of whisky and the windbag rhetoric of SNP leader Alex Salmond is nothing short of a bagpiper’s dream.

Yet, a couple of opinion polls this month have indicated the verdict could go in the separatists’ favour. Such a narrowing from a once runaway “Better together” crusade has transpired because of the complacency and incompetence of the UK government and national political parties.

Last week, in a state of panic, Prime Minister David Cameron rushed to Scotland to remark it will “break my heart” if the region quit the UK. This week, he will warn Scots it is a “once and for all” choice. The fact is Scots are by and large unimpressed by Conservative Party politicians like Cameron. And if anyone is going to make a difference over the next few days, it will probably be the Labour Party, which has been the main political force in Scotland for decades and is still the principal challenger to the SNP.

Without waiting for the crisis to deepen, Cameron’s immediate predecessor Gordon Brown, Labour and a Scot, embarked on whistle stop tour to rescue matters. J.K. Rowling, Scotland’s most successful novelist, who donated one million pounds (around $1.6 million) to the status quo efforts, simultaneously tweeted “reason not ranting, unity not enmity”.

A narrow win will be a hollow victory for Cameron, whereas the slimmest of margins will be a massive triumph for Salmond.

India’s External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj may have been undiplomatic in uttering “God forbid!” in response to a question on the referendum, but in so doing she unwittingly declared what should privately be India’s position. Success of the Scottish project could lead to uncomfortable international pressure on New Delhi vis-a-vis secessionists within its soil.

Besides, the 503-million people common market is the biggest incentive for Indian companies to invest in Europe. They wouldn’t exactly be queuing up to locate themselves in Scotland if it no longer enjoys free trade with either the UK or the EU.

(The views expressed here are personal)