By C Uday Bhaskar

By C Uday Bhaskar

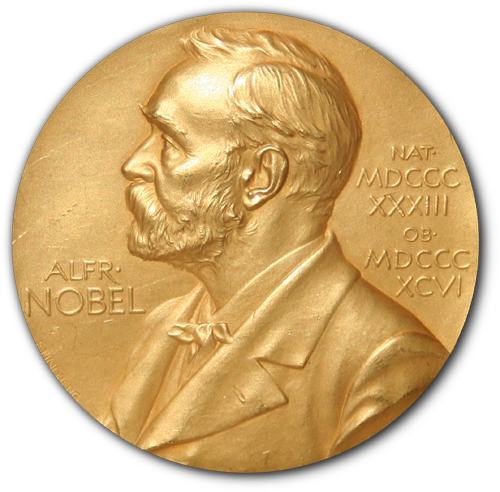

In a surprise announcement, India’s little-known child rights adherent Kailash Satyarthi and Pakistan’s Malala Yousafzai have together been awarded this year’s prestigious Nobel Peace Prize “for their struggle against the suppression of children and young people and for the right of all children to education”.

This prize assumes significance not only because this is the first time that the legacy of Mahatma Gandhi (who incidentally did not receive the Nobel) has been acknowledged by the Nobel committee. Concurrently, it is a first for Pakistan, in that a young girl internationally recognized for braving a brutal Taliban attack and who remains committed to education for the girl-child has been awarded the coveted prize.

But this joint award is even more ironically poignant, coming as it does when India and Pakistan are engaged in an intense exchange of ordnance across the contested Line of Control in Jammu & Kashmir and heavily guarded International Border. The fact that innocent civilians have been killed on both side underscores the imperative of nurturing peace on the sub-continent despite the revisionist agenda of the ‘deep-state’ in Pakistan.

Kailash Satyarthi has been active in the movement against child labour since the 1990s. His organization Bachpan Bachao Andolan has freed thousands of hapless children from various forms of servitude and helped in their successful re-integration, rehabilitation and education.

The Norwegian Noble committee awarded the peace prize to Kailash Satyarthi for showing great personal courage and strength. The committee noted that Satyarthi followed the great tradition of Mahatma Gandhi and has headed various forms of peaceful protests and demonstrations, focusing on the grave exploitation of children for financial gain. The Committee further added: “His contribution towards the development of important convention on child’s rights is immense.”

In relation to Malala Yousafzai, it was observed that she has shown by personal example that even children and young people can contribute to improving their own situation. It is pertinent to note that Malala has worked under the most dangerous situations and the citation said: “Through her heroic struggle, she has become a leading spokesperson for girls’ right to education.”

An exile of sorts, who cannot return to her country because of the Taliban threat, Malala’s choice for the Peace Prize draws attention to Pakistan’s most severe socio-cultural challenge – that of radical and ideological extremism which, among other inflexible strictures, forbids girls from obtaining education. Malala herself is a victim of such radical extremism and was shot at by the Taliban in 2012 for supporting girl’s education and protesting against curbs imposed by extremist forces.

On the other hand, in India, though gender-equity is not as distorted, the status of children in general and women in particular leaves a lot to be desired. The shameful Nirbhaya case of December 2012 is illustrative. The plight of young children who are forced into employment that often takes the form of servitude bordering on bonded labour is one of India’s glaring omissions. Estimates of the total number of Indian children who are forced into labour vary from 12 to 17 million – and this is deplorable.

Satyarthi symbolizes the quiet one-man crusade against this form of exploitation and hopefully the Nobel prize (despite its incongruous reference to the Hindu-Muslim identity of the awardees) will focus much needed attention and spur a more concerted collective effort in this regard.

The improvement of basic human security indicators which includes a secure future for children and the removal of misplaced cultural taboos that target girls and women is a challenge for large parts of southern Asia. In their respective trajectories, both Satyarthi and Malala have emerged as role-model crusaders for the struggle against suppression of children and young people.

As the guns remain silent and an uneasy peace prevails on the India-Pakistan border, hope for that abiding peace remains elusive. Perhaps it may yet filter through the many tears that scar the faces of the oppressed children of the sub-continent.

That the sub-continent still has a wry sense of humour is summed up in this lighter vein quip from Pakistan doing the cyber rounds:

“When Pakistan is getting its first Nobel Peace Prize, an Indian comes and steals half of it. I’m going to call one half of the 2014 Nobel Peace prize as Azad Nobel Peace Prize and the other half as Indian Held Nobel Peace Prize.”