By Saeed Naqvi

By Saeed Naqvi

On March 10, 2014, President Pranab Mukherjee had promised a Citizens Group for 1857 that he would obtain from the government details on how India’s First War of Independence will be commemorated. A change of government may have delayed the inquiries Rashtrapati Bhavan intended to make.

Meanwhile, another anniversary will have gone unnoticed.

On May 11, 1857, soldiers of the British Indian Army reached Delhi after having captured Meerut Cantonment a day earlier. Most soldiers were Hindu. Their uprising had wide support among the peasantry. They identified Bahadur Shah Zafar, the Moghul Emperor, as the symbol of their struggle. They proclaimed him Emperor of Hindustan. This was the secularism of common aspirations and a united struggle.

The uprising had been building up. In a sense the British annexation of Awadh and arrest in 1856 of the popular King of Awadh, Wajid Ali Shah, caused it to spread. The King was exiled to Matia Burj, outside Kolkata.

It is true that powers of Indian rulers had been greatly diminished once the British were ascendant after the battle of Plassey in 1757. About the same time, Ahmad Shah Abdali was menacing Delhi.

In the shadow of the Afghan and British threats the remarkable cultural activity in the courts of Delhi and Lucknow was quite extraordinary. In fact the esteem in which some of these kings were held by their subjects came in for laudatory mention by the then leader of opposition in the House of Commons, Benjamin Disraeli. He was appalled that the British resolve on “divide and rule” had weakened. The uprising itself was proof enough. Hindus and Muslims joining hands against the British in 1857, he argued, was a dismal failure of His Majesty’s government in India.

This “joining of hands” in a common cause was seen by colonial authorities as a serious threat. Surely it is worthy of being commemorated on a national scale. Should 1857 be celebrated as a great national event, vistas would open up for many subsidiary commemorations.

Zafar was exiled to Yangon where he was incarcerated in the garage of a junior British officer where he died. His grave, in a secret location, was discovered much later.

The British ultimately crushed the Indian uprising, marvelously described in William Dalrymple’s, “The Last Moghul”. The first Indian Editor to face the cannon not far from Chandni Chowk was Maulana Baqar Ali. Delhi’s Press Fraternity might like to take up that theme.

Earlier in its innings, the United Progressive Alliance tossed up a plan to observe the 150 years of 1857 on a spectacular scale in 2007.

Towards this end, in 2006, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh called a meeting at his residence of all senior political leaders, artists, social workers, journalists, to chalk out a programme of action for the commemoration in 2007.

Sonia Gandhi, L.K. Advani, A.B. Bardhan, Prakash Karat, Mulayam Singh Yadav, Lalu Prasad, Nitish Kumar, Gandhian Nirmala Deshpande, Jawed Akhtar and a host of others including yours truly were present.

Several ideas were accepted. For instance, the entire route from Meerut be decorated by setting up memorials. What would these memorials be? Details could be further discussed.

An idea which received unanimous approval was the one spelt out by Nirmala Deshpande – that Zafar’s remains be brought to India. It would be a lovely idea because the poet king had marked out a burial place for himself near the shrine of his spiritual Guru, Sufi Saint Khwaja Bakhtiar Kaki in Mehrauli.

He had lamented in a famous verse:

Kitna hai badnaseeb Zafar

Dafn ke liye

Do gaz zameen bhi na milee

Kooye yaar mein.”

(Even in his death, Zafar is so unfortunate;

He could not find two yards of land in his beloved country)

It would be a stirring home coming for the poet-king, if Nirmala Deshpande’s wish were to be fulfilled. To help support her idea was a hint from the government of Myanmar three years ago. Just at the time that Zafar was transported to Yangon, the king of Mandalay was exiled to Ratnagiri in Maharashtra. There were newspaper reports that the Myanmar government may be interested in discussing a swap. It is a wonderful idea but probably cumbersome.

A more feasible proposition would be to bring a fist full of earth from Zafar’s grave and give it a symbolic burial in the grave in Mehrauli he had readied for himself.

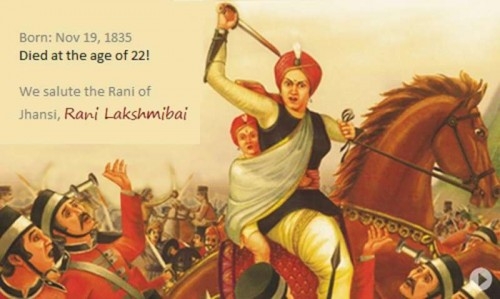

Memories of 1857 can yet inspire in other ways too. Would not the empty canopy at India Gate provide just the pedestal for a well chiseled, marble statue of Rani Laxmi Bai of Jhansi on her horse. We almost owe it to her because her embroidered Insignia, with an image of Hanuman dominating it, was stolen from the regimental centre of Rajputana Rifles, where it had been placed for safe keeping.