Vikas Datta looks into the writings of Ryszard Kapuscinski

Journalism, or especially news reporting, is a rather ephemeral form of literary expression, concerned as it is with bare facts of a developing situation in a terse and concise style. But there are practitioners of the craft whose reportage is no less a work of literature – like this intrepid, peripatetic Polish reporter, whose coverage of Africa (and its messy experience of colonialism’s end) and Central America was unparalleled and enduring, and made him a credible contender for the Nobel Literature Prize.

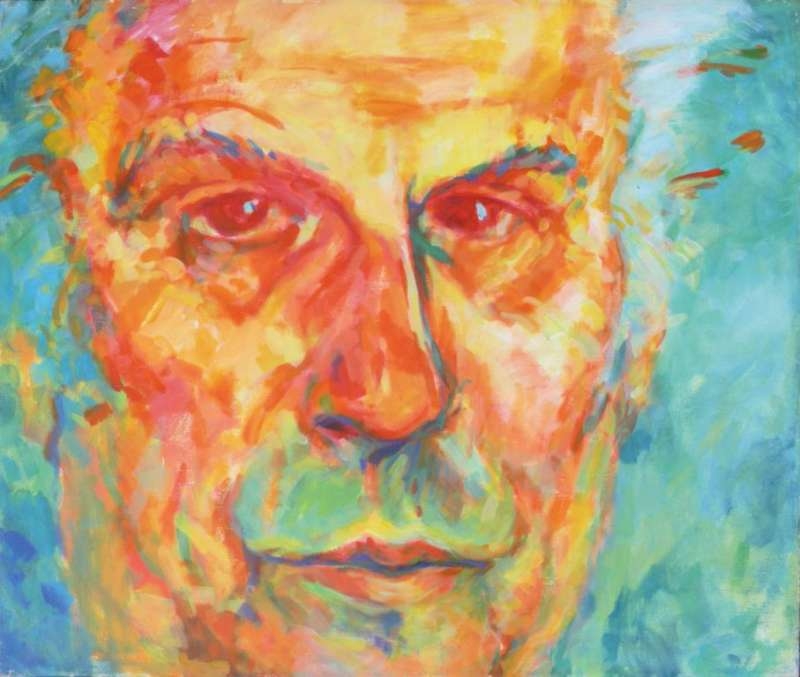

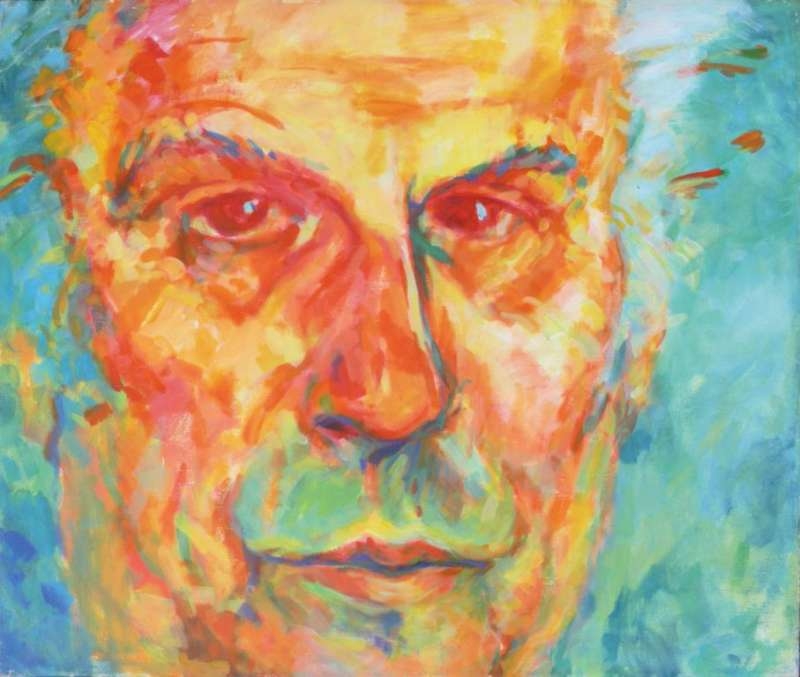

Ryszard Kapuscinski (1932-2007), who acknowledged the great influence of his celebrated compatriot Joseph Conrad (Jozef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski), did also in his writings stress the lack of difference between “civilisation” and barbarism – and the trials and resilience of the human spirit in indifferent or even unforgiving environs.

He had these experiences enough – in 27 revolutions and coups, in wars after colonial rule ended or even contentious sporting encounters, 40 spells of imprisonment and four death sentences. In addition, there were venomous animals, debilitating diseases, endemic violence and other hazards in his realm of work which spanned quite a bit of the Third World across three continents.

In his two dozen-odd books, standing out with their psychological insight and vivid description (like Conrad), sophisticated style of narration, and unusual imagery, Kapuscinski sketched incisive accounts of key, but under-served, figures, events and countries – Ghana and Kwame Nkrumah, Congo and Patrice Lumumba, Algeria and Ahmed Ben Bella, the “Lion of Judah” or Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie, and Iran’s Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, among others.

But what chiefly sets him out is his pioneering account of the initial exultation and optimism of an Africa emerging from colonialism – and the all-too rapid disintegration into despair, disillusionment and listlessness as only corruption, poverty and conflict ensued.

Starting his career with “Sztandar Mlodych” (“The Banner of Youth”), the mouthpiece of the ruling Communist Party’s youth wing in 1950, Kapuscinski was sent to India in September 1956 – with his boss gifting him a Polish translation of Herodotus’ “Histories”. (This accounts for the name of his book on his experiences of Asia: “Travels with Herodotus”, 2007; Polish “Podroze z Herodotem”, 2004). In India, he began to learn English by reading Hemingway’s “For Whom the Bell Tolls”. Returning home after a stint in China, he joined Polska Agencja Prasowa (the Polish Press Agency) in 1958 and was sent to Africa to cover 50 countries.

Shifted to South America in 1967 and then Mexico, he returned to Africa in 1975 to cover the last European decolonisation – the Portuguese withdrawal from Angola – and the start of a long, brutal civil war that later drew in apartheid-era South Africa and Fidel Castro’s Cuba. His three-month stay (which included lengthy travels) there is recounted in the haunting “Another Day of Life” (1987; “Jeszcze dzien zycia”, 1976).

Trips to Ethiopia (1975, 1977) in wake of the overthrow of long-time monarch Haile Selassie resulted in “The Emperor: Downfall of an Autocrat” (1983, “Cesarz”, 1978), about a ruler living in unimaginable luxury while his subjects faced hunger and starvation. Containing accounts from the former ruler’s entourage (including one who had to wipe shoes of dignitaries on which the emperor’s favourite dog had urinated), it was the first of his works to to be translated into English and one that brought him to attention in the West – especially with the parallels to then Communist world.

The succinct “Shah of Shahs” (1987, “Szachinszach”, 1982) about Iran’s 1979 revolution also includes a prescient forecast of what would ensue, while “Imperium” (1993, both Polish and English) is about his experiences of the Soviet Union in its heyday, during its collapse and then in new Russia and other former republics.

But it is Africa where Kapuscinski felt most at home because “food was scarce there too and everyone was also barefoot” that accounted for some of his best writing.

The continent occupies most of “The Soccer War” (1990; “Wojna futbolowa”, 1978) – named from his account of the short but no less bloody 1969 war between Honduras and El Salvador triggered by a football match, though thus sharing space with Latin America, as well as the Middle East and even Cyprus. “The Shadow of the Sun” (2001; “Heban” (literally ‘Ebony’) 1998) is fully devoted to Africa, moving in time and space from 1950s Ghana to Rwanda (with an incisive analysis of the genocide) and Tanzania in the 1990s.

The veracity of some of these accounts has been questioned but Kapuscinski himself described them as “literary reportage” and their strength lies in being illustrative readings than fully factual and exhaustive accounts or analyses, intended primarily to draw focus to some ignored, miserable places – and succeeding if you see the number of books now on the subject!