By Andres Sanchez Braun

By Andres Sanchez Braun

Japan’s first virtual school, where teachers and students interact through avatars on the internet, just opened its cyber-doors, seeking to offer an alternative education to “hikikomori”, the Japanese word referring to sufferers of an anxiety disorder similar to agoraphobia, where people isolate themselves from others.

A total of 204 students enrolled in the first term, which started on April 24, for the annual fee of 180,000 yen ($1,500).

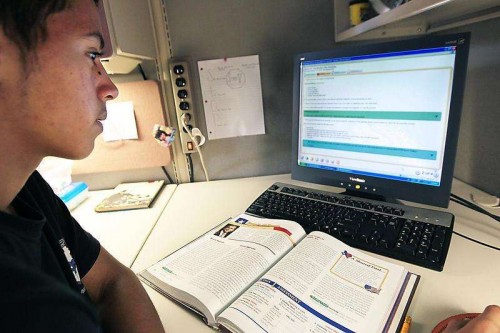

The customisable avatars are distinguishable by the nearly infinite selection of hairstyles and clothing accessories, not unlike characters from Japanese role-playing games or Nintendo Mii avatars. It is mandatory for students to attend classes regularly — through software installed on their personal computer, tablet or mobile phone — at their new school on the web.

The programme allows students to direct their avatar through the campus, going to classes (consisting of 20-minute videos and a written exam), consulting audiovisual material or e-books in the media library, or interacting with the avatars of fellow classmates and teachers through a chat interface.

This virtual school was created by Meisei High School, a private institute in the Chiba region, which has for several years been offering distance learning programmes for baccalaureate degrees.

The 20 face-to-face tutorials throughout the academic year required by the distance learning programmes, however, still posed difficulties, and thus inspired the idea for this alternative, virtual project.

A hikikomori, according to Tamaki Saito, the Japanese psychiatrist who coined the term, is a person who does not show any psychotic symptoms but remains isolated from all social contact — except for minimal interactions with his or her family — continuously for more than six months.

Many of the afflicted — mostly men — may shut themselves in their rooms or apartments for years or even decades no end, making little to no contact with the outside world.

Meisei’s virtual school requires fewer face-to-face interviews (only four in every term), and at the same time seeks to promote interaction, though only through a screen.

“The distance learning education system forces an individual to study alone for many hours at home, making it difficult to sustain motivation levels and favouring loneliness,” Masaki Shimoda, professor and director of studies at the school, who also has his own avatar, told Efe news agency.

“That is why we have started this programme which, despite being one of distance learning, allows communication with students and teachers,” he added.

Students who successfully complete the three-year term in the cyber-school will get a high school diploma, regardless of their age.

Some people have warned of the negative effects of such an initiative on social recluses, as the approach is very different compared to most treatments used by therapists or NGOs who work with hikikomoris.

Shimoda however defended the project, saying it gave equal importance to academic curriculum and has the same goal as other educational institutions: to “promote personal growth of the students so that they can integrate in society after leaving the institute”.