Half a century after the formation of the Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPI-M), the curtains are descending on what the comrades once saw as the beginning of a Leftist transformation of India.

Half a century after the formation of the Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPI-M), the curtains are descending on what the comrades once saw as the beginning of a Leftist transformation of India.

In the years soon after the 1964 split in the undivided Communist Party led to the CPI-M’s birth, a senior leader of the Marxists, M. Basavapunniah, noted the Congress’ decline – the latter has always been waxing and waning – and said: “We will not feel happy if this party goes down without the emergence of a viable democratic alternative.”

According to him, “such a situation will help imperialist and regressive forces to dismember the country. Our concern for the Congress is because it affects our future. We want to take over a united and not a fragmented India.”

This overweening confidence stemmed from the belief, as spelt out by a CPI-M central committee document, that “Marxism-Leninism is a (an) inexhaustible spring that can nourish socialism’s new thrust forward”.

One reason, however, why the “thrust” never materialized was that the CPI-M itself fell apart when the extremists in its ranks, the Naxalites (as Maoists were known then), left and formed their own outfit in 1969.

Commenting on this “Left deviation”, the CPI-M ruefully noted how “a section of party leaders and cadres were carried away by the Left adventurist point of view advocated by the Communist Party of China. Thus, the two successive splits (in 1964 and 1969) sapped the strength of our party”.

However, the fact that notwithstanding this diminution of its strength, the CPI-M did make a recovery in the 1970s pointed to a fairly wide measure of popular support for it even if this was confined to the states of West Bengal, Kerala and Tripura.

At the same time, the party’s gains were due more to the Congress’ follies than to its own endeavours. For instance, but for the “excesses” of the Emergency in 1975-77, it is unlikely that the CPI-M would have been able to dislodge the Congress from these three states in 1977.

It is the stints in power, however, especially in West Bengal, where the CPI-M had an uninterrupted 34-year reign from 1977 to 2011, which can be said to have led the party into a blind lane.

The reason is that it turned out to be no different in terms of administrative aptitude or ethics from its “bourgeois” adversaries. The earlier claim, therefore, that the party was engaged in ending the “exploitation of man by man inherent in capitalist production” was no longer believed even by its own supporters.

Hence, the sardonic observation of a fellow traveller, Samar Sen, editor of Frontier, that if the revolution continued after 5 p.m., the workers will ask for overtime payment.

It isn’t only the negation of the CPI-M’s assertion of being a party with a difference – echoes of a similar claim by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) – which led to its downfall but also the fact that its cadres acquired the reputation of being hooligans, one of whom, wearing a helmet, had assaulted Mamata Banerjee (then a Congress leader) on Aug 16, 1990, at a prominent street crossing in front of police and media personnel.

The year is significant because, a year earlier, the Berlin Wall had fallen, denoting the terminal stage of Communism and, a year later, market-friendly policies were introduced in India. These two doctrinal and economic changes were beyond the CPI-M’s capacity to withstand.

As it is, the party had been rocked by previous upheavals in the Communist world, notably by Nikita Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization speech in 1956 and by the Sino-Soviet rupture at about the same time, which was behind the splits in the Indian Communist parties as well.

But even if these events did not undermine the CPI-M’s belief in the veracity of “scientific socialism”, they shook the faith of a large body of its supporters in India. The ease with which it could earlier rally thousands to respond to its calls such as “amar nam, tomar nam, Vietnam, Vietnam” was no longer possible because the middle class, which had been its main base of support in West Bengal and elsewhere, had drifted away.

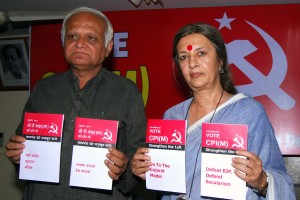

But it was the economic liberalization which accelerated this exodus. As CPI-M general secretary Prakash Karat noted after the party’s setbacks in the 2009 general election, there was “a disconnect between the Left and sections of the middle class”.

Moreover, this disconnect was more pronounced in the case of the “young who had benefited post-reforms in terms of better opportunities, jobs, income”. Not surprisingly, the CPI-M suffered even greater setbacks in this year’s general election, with its tally of Lok Sabha seats dropping from 16 in 2009 to nine.

Since governments in New Delhi, whether led by the BJP or the Congress, are likely to continue to favour an open economy, there isn’t much chance of the CPI-M, and of the Left in general, improving their position as they fight the lost wars of the dead Soviet Union against American “imperialism”.