Saeed Naqvi writes about the the west’s imminent nuclear deal with Iran

Saeed Naqvi writes about the the west’s imminent nuclear deal with Iran

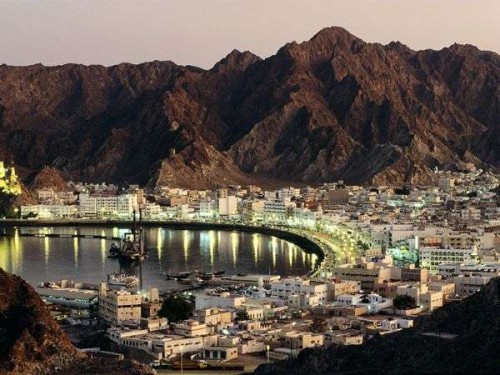

The picturesque Sultanate of Oman was set to make history. It was to be the venue where the West would conclude its nuclear deal with Iran. But control of both the Houses of Congress by Republicans has swelled the ranks of anxious busy bodies darting around the world’s chanceries to sow doubts about the deal.

That an agreement was round the corner was known for weeks, even months. But the most recent tell-tale expression of the West’s intent appeared on the cover of The Economist last week. In the photograph of Ayatollah Khomeini the magazine carries on its cover, the founder of the Islamic revolution’s marble face has cracked with age. From the crevices in the visage, doves of peace are flying in all directions. The photograph which represents both, symbolism and hyperbole, is mounted by a headline: The Revolution is Over.

This is the West’s pre-emptive spin. In the West-versus-Iran confrontation, who blinked? First, of course, are a host of very technical nuclear related issues which will set the region at rest about Iran’s military ambitions. But an agreement that could well be signed will, most importantly, carry an overriding political message.

The message on The Economist cover is straightforward. Iran has exhausted its revolutionary fervour and is now a status quo power. It has been transformed into a clubbable state. There are fears, however, that the new Republican-dominated Congress will nevertheless insist on retaining stringent sanctions on Teheran even after an agreement has been reached. This could be a deal breaker.

If Republican clout in the US Congress retards progress on the nuclear track with Iran, misgivings about Washington’s ability to act on a host of issues will multiply. The reliability quotient of the West in general will further diminish.

Secretary of State John Kerry was upbeat in Paris earlier in the week. “I want to get this done,” he told French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius, a consistent friend of Israel. Should the Congress hardliners retard the deal at this late stage, Fabius will thumb his nose at Kerry – and the world at Obama.

As it is, there are deep suspicions in diplomatic circles about the overall American intentions in West Asia. Americans are in the region, says one Arab diplomat in ringing tones, because their faith is shaken in the Israeli capacity to control the region after the recent 50-day Gaza war. This dictates reorganizing the West Asian chess board in which Iran must be brought in as a central player.

President emeritus of the Council on Foreign Relations, a former New York Times columnist and Senior Defence and State Department official, Leslie Gelb, wrote last month: “US leadership has since the Iranian revolution in 1979 singled out Iran as the locus of all evil”. In a dramatically changed situation today, both Iran and the US, see the “Sunni jihadis who threaten the interest of both”.

The common cause the US can make with Iran extends to other theatres of conflict – Pakistan and Afghanistan for instance. “The only serious conflict is over Israel.” Gelb does not see that as an insurmountable obstacle.

Traditionally, Iran and Israel have not been foes. Quite the contrary. “The US strategy should be to use cooperation in other areas to ease Teheran’s hostility towards the Jewish state.”

This line of thinking is gaining widespread currency. And it is not good news for Saudi Arabia. But Riyadh should draw comfort from the fact that powerful factions in Teheran, like former president Hashemi Rafsanjani, consider the present Saudi regime a much more acceptable proposition compared to what might follow if the present regime goes. In the cloak and dagger world of West Asian politics, a theory given credence to by all non-GCC Arabs is precisely this: the regime in Riyadh is mortally afraid of the ISIS. There are two Sunni streams in the ISIS which are hostile to monarchies as being anti-Islamic. These two schools are the Muslim Brothers and Al Qaeda.

With what alacrity did the Saudis turn up in Cairo with $12 billion cheque for the then General Abdel Fatah el-Sisi for having ousted President Mohamed Morsi, the emerging Muslim Brotherhood icon.

Equally revealing was the composition of the initial “coalition of the willing” against the ISIS – Jordan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain. In other words the monarchies and the Sheikhdoms.

The ISIS push towards key cities in Syria and Iraq has been halted because of tacit US-Iran cooperation. Whatever the level of agitation in the Republican-dominated Congress, steps in this direction are not likely to be reversed in a hurry.

Yes, a redistribution of power in West Asia is clearly on the cards. The Shia Houthis in Yemen, for instance, now in control of Sanaa, lean heavily on Iranian support. This ground reality will in all probability be allowed to prevail in the near future. Then there is the totally untenable situation in Bahrain where the King stands in opposition to 90 percent of the population who happen to be Shia.

In 2011, US diplomat Jeffrey Feltman had very nearly brought about a compromise between Bahrain’s Crown Prince Salman bin Hamad al Khalifa and Shiekh Salman of the Shia Wefaq party. But Bahrain’s prime minister colluded with the hard line Saudi Interior Minister, the late Prince Nayef bin Abdel Aziz, and GCC tanks rolled down the 37-km causeway linking Bahrain to Saudi Eastern province where the country’s main reserves of oil coexist with a restive Shia population. It is getting so complicated for the Saudis, simultaneously facing a fierce succession struggle, that an honourable adjustment with Iran, possibly under US auspices, looks like the only sensible way out of the jam.