M.R. Narayan Swamy reviews Kanshiram by Badri Narayan. The book is a tribute to an Indian leader who re-invented Ambedkar to mesmerise Dalits

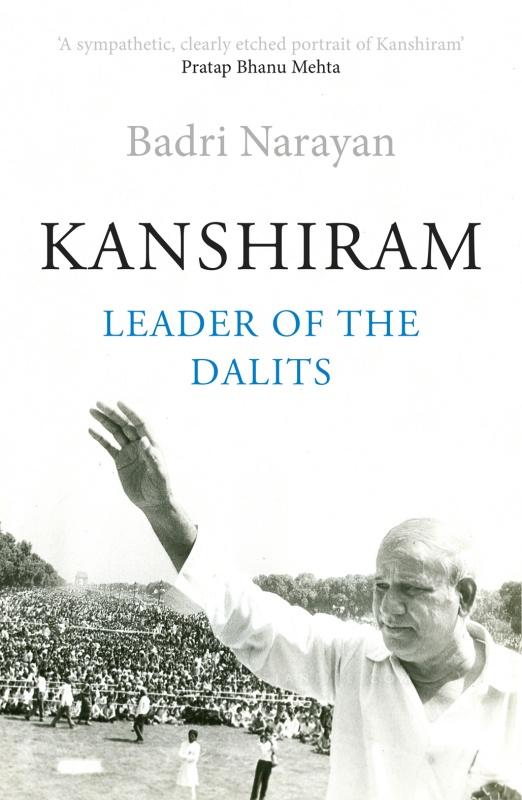

BOOK: Kanshiram: Leader of the Dalits; Author: Badri Narayan; Publisher: Penguin/Viking; Pages: 265; Price

BOOK: Kanshiram: Leader of the Dalits; Author: Badri Narayan; Publisher: Penguin/Viking; Pages: 265; Price

Kanshiram was to Dalits what Narendra Modi is for Hindutva – an icon. Much like Modi, Kanshiram struggled from an early age to ultimately make a mark in politics. But the struggle was much harder for this sturdy ‘Chamar Sikh’ from Punjab with a Hindu name.

Unlike Modi, Kanshiram had no political party to lean on. After backbreaking efforts, he founded one, the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), which, in just a short period, ended up as one of India’s major political formations, shaking up the Congress in the state which matters, Uttar Pradesh, and beyond. This book is the first major – and very rich – biography of Kanshiram, who, on the road to success, boasted: “Ambedkar collected books, I gathered people.”

Unlike most political leaders, Kanshiram sacrificed everything he had for a cause he held dear: help Dalits lead a better life. A science graduate, he quit as a Class I officer in a government establishment in Pune after fighting to restore Ambedkar Jayanti and Buddha Jayanti as official holidays. He joined the Republican Party of India but quit in disgust despairing over its lack of militancy. Kanshiram was very clear: “Rights are to be seized, not requested for.” It is a thinking that shaped his life.

The victory in Pune led Kanshiram to plunge into Dalit literature and Dalit politics in real earnest. Taking measured steps, he founded the Backward and Minority Communities Employees Federation (BAMCEF) to rally lower caste government employees. He also took a momentous decision – rare in politics – to cut off all ties with his family. He pledged never to return home, never to marry, never to take part in social gatherings, never to take up any other job, and “not rest in peace till Balasaheb Ambedkar’s dream had been fulfilled”. Kanshiram kept his word. When his father died, he didn’t go home to perform, as the eldest of seven children, the last rites; these were done by a younger brother.

As an activist, he was humbleness personified. When he travelled to mobilize Dalits, he would eat at homes of fellow activists; not spend public money on hotels. With his chosen comrades, Kanshiram moved from place to place with just a bag containing a set of clothes and some items of daily use. He travelled on trains in general compartments, “enduring all the dirt, dust, heat and cold”. If tired, he would put his slippers in his bag and use it as a pillow to take a nap. He dressed simply, in half-sleeve shirts and trousers, at times buying them from markets selling second-hand garments. He made his own slippers out of rubber tires. Once someone picked Kanshiram’s pocket, leaving him with no money for a tonga ride from a railway station; so he walked 15 km to deliver election posters to a village. Kanshiram’s devotion gave the BSP a solid foundation that survives to this day.

As his reputation spread, BAMCEF attracted tens of thousands of the best of Dalits – PhD scholars, scientists, doctors, government staff et al. Kanshiram held seminars and rallies. He re-created forgotten Dalit saints and heroes including from the 1857 revolt. He popularized Ambedkar in Uttar Pradesh like never before. BAMCEF (formally born in 1978) was followed in 1981 by the more political Dalit Shoshit Samaj Sangharsh Samiti or DS4, whose membership was open to all except Brahmins, Kshatriyas and Banias. A 1983-84 all-India cycle rally by some 300,000 DS4 activists was Kanshiram’s first show of strength.

Kanshiram was no blind follower of Ambedkar. Unlike Ambedkar who stood for annihilation of caste, Kanshiram utilized the caste divisions to his advantage, building a broad platform of lower castes to derail traditional parties and sought to take control of governments. It was a bold move that paid great dividends. Again, unlike Ambedkar, Kanshiram never converted to Buddhism – probably he was afraid of offending the “Chamar Hindus” of Uttar Pradesh.

DS4 led to the BSP in 1984. In no time the new party outpaced both the Congress and the BJP in Uttar Pradesh. Making use of opportunistic alliances, he installed Mayawati as the country’s first Dalit chief minister in Uttar Pradesh. In 2001, due in part to growing internal differences within the party and to failing health (the feverish pace of work led to diabetes and high blood pressure), Kanshiram bequeathed the BSP leadership to the young Mayawati. In 2003, he suffered a brain stroke, and died three years later amid allegations that Mayawati had held him a prisoner.

Kanshiram succeeded where even Ambedkar failed: stitching together a fighting Dalit network. It was no easy task. It was a self-made man who aroused the Dalits. That the BSP has its limitations even vis-à-vis Dalits is another story. One does wonder if Kanshiram would be happy to see the BSP – and Mayawati’s lifestyle and politics — of today. This book must be read by every student of Indian politics.