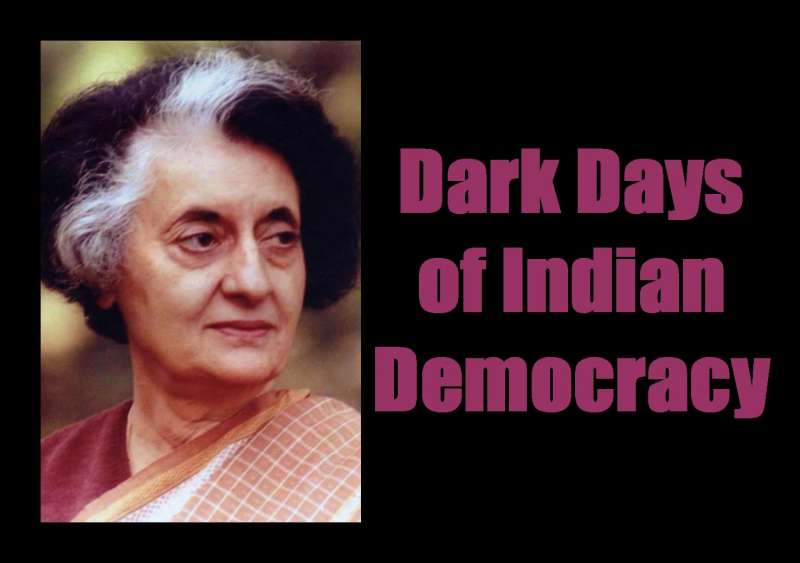

Saeed Naqvi looks in to Indira Gandhi’s Emergency regime which has changed the landscape of Indian politics. Visit asianlite.com for latest news and comments

Of course there was an Indian, regional and global context in which Indira Gandhi declared a state of Emergency on June 25, 1975? The 70s were a decade of fierce contest between the West and the Soviet Union. The Cold War was going badly for the West – Vietnam, Angola, Mozambique, Ethiopia, Nicaragua had all returned Communist governments.

Of course there was an Indian, regional and global context in which Indira Gandhi declared a state of Emergency on June 25, 1975? The 70s were a decade of fierce contest between the West and the Soviet Union. The Cold War was going badly for the West – Vietnam, Angola, Mozambique, Ethiopia, Nicaragua had all returned Communist governments.

The June 14, 1976 cover of Time magazine had a menacing photograph of Italian Communist leader, Enrico Berlinguer with a headline in thick, red fonts: The Red Threat. Franco and Salazar had died, leaving Spain and Portugal exposed to the blandishments of the Left. Secretary general of the French communist party, George Marchais was a formidable force.

Baath socialists in Baghdad and Damascus, pro-Soviet regimes in Algeria and Libya – all tended to give the balance of advantage to Moscow, even though the US had scored a major victory by having Anwar Saadat sign the peace accord with Israel in 1979.

Stand-alone comedians in Washington continued to titillate the audience on detente which, at that stage was going badly.

The US had learnt its lessons in Africa, West Asia and Latin America. In many countries listed above there were either nascent or full blown communist movements or anti American regimes like the ones in Baghdad, Damascus, Tripoli and Algiers.

The Shah of Iran’’s Secret Police, Savak, dreamed up a plan to eliminate the Left – Khalq, Parcham and a latent Shola e Javed – from around the establishment in Kabul. Accidental death of a trade union leader, Mir Akbar Khaibar, resulted in the plan being exposed. Communists, Aslam Watanjar and Abdul Qadir of the Afghan armed forces, acted pre-emptively. They trained their tanks on President Daud and his close supporters who were killed in the palace. Nur Muhammad Taraki of Khalq became prime minister. This happened in April 1978. In Islamabad, Zulfiqar Ali BhuttoÂ’s judicial assassination inaugurated the era of Zia ul HaqÂ’s Islamism. The Ayatullahs came to power in Tehran in 1979.

Where was India in all of this? It turns out that the intense east-west contest of the 70s may well have begun in India. In 1969, Indira Gandhi split the congress along ideological lines. The right wing, business friendly party bosses, the Congress (O), searched for and found like-minded groups they could coalesce with – Jana Sangh (which later became the BJP), RSS, (BJPÂ’s ideological mentors), Socialists (in their anti communism, close to all the groups listed above), and the professional Gandhians, Hindu and austere.

This coalition acquired urgency because Indira Gandhi had begun to lean directly on the Communist Party boss, S.A. Dange. Colleagues like Mohan Kumaramangalam, P.N. Haksar were strong leftist influences on her.

Global moves, counter moves were on. Henry Kissinger was plotting a Washington, Beijing, Moscow triangle. Just then the Indo-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation was signed. With Soviet help, India liberated Bangladesh.

Global moves, counter moves were on. Henry Kissinger was plotting a Washington, Beijing, Moscow triangle. Just then the Indo-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation was signed. With Soviet help, India liberated Bangladesh.

On the one hand, India was now in a vice-like grip of the Soviet Union, on the other, Secretary General of the Communist party in Bihar, Jagannath Sarkar, had taken up the land question with sufficient success to worry the Congress.

Between the Deendayal Upadhyay Institute in Jhandewalan, Gandhi Peace Foundation and Ram Nath GoenkaÂ’s apartment in the Indian Express building, a scheme was hatched to resurrect Jaya Prakash Narayan as a counterpoint to Indira Gandhi who seemed invincible after the Bangladesh operations.

Anti Vietnam war youth movements at Grosvenor Square, London, the barricades in Paris building upto the Kent State university shooting in 1970 which killed four anti Vietnam (Kampuchea) war protestors, were far away to infect youth movement in India. And yet, by 1973 a powerful youth movement was taking shape in Gujarat ignited by students. They were protesting against inadequate hostel facilities. Mysteriously, the dissolution of the state assembly became a prime demand. The Congress (O) leader Morarji Desai went on indefinite hunger strike. The assembly was dissolved. Agitationists had tasted blood.

JP, ofcourse, had visited Gujarat to pick up tricks he might employ in the Bihar agitation which initially targeted the countryÂ’s most innocuous chief minister, Abdul Ghafoor. JP invited Morarji Desai to be chairman of the Sangharsh Samiti (Action committee). The senior most RSS leader Nanaji Deshmukh, was its convener.

It was Naanji Deshmukh and his RSS cadres on whose shoulders the Bihar movement was carried. JP had very kindly invited me to stay with him in his family house in Kadam Kuan. I therefore had a ringside seat on the JP movement.

Peter Hazlehurst of The Times, London, described Indira GandhiÂ’s politics in a pithy phrase: she is a little left of self interest.

It was her dependence on the left and the Soviet Union, that the JP movement sought to bring under strain.

Relentless pressure was kept up, first by a successful Railway strike in May 1974 led by the firebrand George Fernandez. The Allahabad High Court judgement of June 12, 1975 unseated her from parliament for misuse of office during her election to parliament.

On June 25, an unnerved Indira Gandhi, imposed the Emergency.

When elections were held in 1977, the electorate trounced Indira Gandhi. The coalition woven by JP during the Bihar movement came to power in Delhi as the Janata Party under Morarji Desai. Atal Behari Vajpayee, L.K. Advani, Murli Manohar Joshi became ministers. Indian politics had taken a turn it was not going to recover from in a hurry.